In 2004 Hampshire Museums Service purchased, with the aid of a Heritage Lottery Fund grant, an archive of photographs, sketches and documents relating to the Tichborne Trials of the late 19th century. Collected by Frederick Bowker, solicitor to the Tichborne family, the archive is the most comprehensive collection of material relating to the case.

The story concerns Roger Tichborne, disappointed in love who is then lost at sea, and a man who, more than a decade later, appears from the Australian outback claiming to be the missing heir. The civil and criminal trials which followed held the record as the longest court case in British legal history until the mid 1990s, and the archive contains photographs of almost everyone involved: - the extended Tichborne family and the Tichborne Claimant, the legal teams on both sides; the witnesses; judges and jurors; and even the court ushers and the boy who sold the newspapers in the street outside.

In an age when forensic science was in its infancy, passports were not always required, and very few people owned any form of personal documentation, the case hinged on the difficulty of proving identity in a court of law. The country was divided, with the Establishment opposing the Claimant but many ordinary people supporting a man who they regarded as being deprived of his rightful inheritance; at one point it was feared that the case might even cause a revolution or civil war.

Read the story below then search the Tichborne Claimant archive and see what conclusion you come to.

The Tichborne Family

The Tichbornes were devout Catholics, which until the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 meant that they could neither stand for Parliament nor become officers in the armed forces. Like other Catholic families therefore, the Tichbornes lived the lives of wealthy country gentlemen, hunting, shooting and amassing land and wealth.

Roger Tichborne

Roger Tichborne was born in 1829, the eldest son of Sir James and Henriette Felicite Tichborne. His mother, Henriette, an illegitimate member of the French royal family, was spoiled, highly strung and loathed England and the rural life with a passion. Henriette took Roger to Paris as a child and he didn't return until he was 16, first to boarding school at Stonyhurst, and later into the army. His holidays were spent with his uncle and aunt, Sir Edward and Lady Doughty, and their daughter Katherine, known in the family as Katty.

Roger and Katty fell in love, but the match was bitterly opposed by both families, not least because they were first cousins. Finally it was agreed that Roger should travel abroad for three years, and that if they still wished to marry when he returned, then the family would raise no objection.

Shipwrecked

Roger decided to sail for the West Indies in the spring of 1854, and managed to take a last-minute passage on board the ‘Bella’. Soon afterwards, the longboat from the ‘Bella’ was found floating in the sea, and Roger Tichborne was presumed dead.

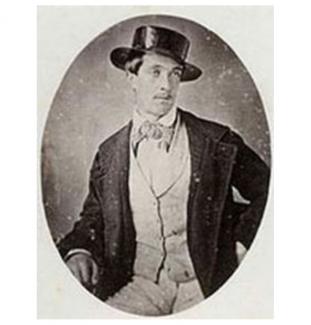

Roger went first to South America, where he travelled for over a year, and where he had two daguerreotype photographs taken of himself. During this time, cousin Katty married Percival Pickford Radcliffe, of a wealthy Yorkshire Catholic family.

Although the ‘Bella’ had been officially declared lost, Roger’s mother was convinced that he was still alive, and placed advertisements in the national and international press seeking information about her missing son.

The Baronetcy

Roger’s younger brother, Alfred, had in the meantime become the 11th Baronet, though his excessive drinking and profligate habits led to his early death at the age of 27, leaving his wife, Theresa, pregnant with their first child.

Roger comes back from the dead

Eventually, in 1866, Lady Henriette Tichborne received the letter she had been hoping for for more than a decade. A man claiming to be Roger Tichborne wrote from Wagga Wagga, in Australia, with a story of having been picked up from the wreck of the Bella and taken to Australia, where he had become a butcher and postman. His story, however unlikely, was given credence because he suffered from the same genital malformation as Roger Tichborne.

Lady Tichborne lost no time and invited the man she believed to be her son, together with his wife and child, back to England. However, because Roger has been declared officially dead, and because Alfred’s wife had given birth to a son, the Tichborne Claimant had to prove his identity in a court of law.

First Trial, the Civic Trial

The first trial, the Civil trial, was intended to prove whether the man from Wagga Wagga was in fact Roger Tichborne. Unfortunately, before the case opened, Lady Tichborne died and his main support was lost, for, as she said, ‘how would a mother not know her own son?’ In order to raise funds for his legal fees, the Claimant began selling ‘Tichborne Bonds’; effectively a gamble on the outcome of the trial, which although they sold for between £40 and £60, were worth £100 out of the Tichborne estate if the case was won.

Costs in the case were considerable, with commissioners being sent both to South America and Australia to find witnesses who might be able to identify the Claimant. During these investigations one name kept appearing; not Roger Tichborne but Arthur Orton of Wapping; son of a prosperous ship’s victualler who had been sent on a long sea voyage in the hope that it would cure him of a nervous condition.

During the trial, the Claimant was asked about the contents of a sealed package that had been entrusted to Vincent Gosford, the estate steward and close friend of Roger Tichborne, before Roger’s departure for South America. In his reply the Claimant alleged that he had had intimate relations with his cousin Katty at Cheriton Mill, and that the package contained instructions for her possible confinement. Such a slur on a lady’s reputation caused an outcry amongst the Establishment, and this, together with the sale of Tichborne Bonds, turned the upper classes into his most bitter enemies. The trial collapsed, the Claimant was declared not to be Roger Tichborne, and was immediately arrested for perjury.

Following his release on bail, the Tichborne claimant began to do the round of the music halls, travelling by rail and addressing huge crowds. Photographs of the Claimant and his family, and of the Tichbornes were collected by many people in much the same way as football cards are today, and these show the Claimant posing as a man of substance and fashion. Even during the second, Criminal Trial, the Claimant was a popular guest at dinners and parties and received ‘fan mail’ from ladies who found him particularly attractive.

Second Trial

This second trial was presided over by Sir Alexander Cockburn, Lord Chief Justice of England, and tried the Claimant on 32 separate counts of perjury. The case became a national sensation, with newspapers bringing out special editions with news of the latest events in the court. Sentenced to 14 years hard labour, the Tichborne Claimant served 10 years and 4 months. He was photographed in his prison uniform, and support for his cause actually increased while he was inside.

Life after prison

On his release, the Claimant spent two more years on the music hall circuit, but gradually interest in the case began to wane, and he travelled to America to try his luck there. The venture was not a success, and he returned to London where he married Lily Enever, a music hall artiste. The couple had four children, all of whom died in infancy, and lived in desperate poverty in London where, on the morning of April 1st 1898, the Tichborne Claimant died in his sleep. The costs of a moderate funeral were borne by the undertaker, and 5,000 people went to the cemetery, with many more lining the route to pay their respects. The Claimant was buried in a pauper’s grave, without a headstone, but the coffin carried, with the permission of the Tichborne family, a plate which read ‘Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne’.