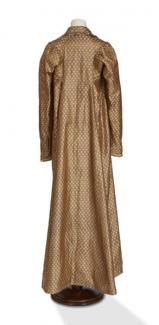

Pelisse, said to have been owned by Jane Austen, woven in silk on a brown gold ground with all over pattern of oak leaf motif in yellow. Dating from around 1814.

'Pelisse' was the contemporary term for this garment, which was popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Changing fashions led to differences in length and cut, but essentially the pelisse was worn over a dress or gown, either as an outdoor garment or for indoor or evening wear depending on the season and the materials from which the pelisse was made. This example is of good quality silk in a twill weave, woven with a small repeat pattern of oak leaves in a golden straw colour on a warm brown ground. The shape of the bodice and skirt, the size of the sleeve heads and the ruched decorative trim suggest a date of c1813-15,

The pelisse has long sleeves gathered at the head but close fitting below the elbow, a high standing collar, and is open at centre front with no fastenings. The front is edged on both sides with bright yellow cord which also appears at the wrists. The gown over which it would have been worn would have shown several inches below the pelisse hem, as well as at centre front and at the cuffs. It is lined throughout with white silk and is, of course, entirely hand made. It is not known where the silk for the pelisse was woven or purchased. However the oak leaf motif was a popular one at the time and symbolised the strength of the Navy and the nation as a whole, especially at a time when the country was at war with France.

The Pelisse and Jane Austen Sadly there is no absolutely definite link between the pelisse and Jane Austen although the family association is quite strong. Jane died unmarried in 1817 and left the bulk of her estate to her sister, Cassandra, who took charge of her papers and other belongings and later distributed them amongst other members of the family. One of Jane Austen’s older brothers, Edward, had been adopted by a distant cousin, Thomas Knight, who had no children and therefore nobody to whom he could have bequeathed the family estates at Steventon and Chawton in Hampshire and Godmersham in Kent. Edward Austen first took the name of Knight in addition to his own, but formally adopted the surname Knight in 1812. Of his eleven children, his daughter Marianne never married but lived at Godmersham with her father until his death in 1852, then with two of her brothers in turn, at Chawton till 1867 and Bentley till 1878, before ending her days with a niece in Ireland. In around 1875 Marianne Knight was visited by a family friend, Miss Eleanor Glubbe, later Mrs Steele. Marianne Knight gave the pelisse to Miss Glubbe during the visit. In later years Mrs Steele wished to return the pelisse to the Austen family and sent it to Mrs Winifred Jenkyns, a great granddaughter of James Austen, Jane’s eldest brother, with a note that reads “I missed the little coat for a long time but lately it turned up. I cannot remember if it was 'Jane's' but it seems probable". This particular pelisse was presumably given to Edward by Cassandra and it would no doubt have brought back vivid memories of Jane wearing it. It was handed down to his daughter, who also loved Jane and spent considerable time with her and could also have seen her aunt wearing it towards the end of her life. That she gave it to her friend, Miss Glubbe, who made sure that it was returned to the Austen/Knight family argues an acknowledged obligation on her part. The pelisse was then handed down through the family until 1993, when it was given to the Museums Service.

Jane Austen lived from 1801 to 1805 in the fashionable spa town of Bath, but even during the time she spent in Hampshire was able to visit London several times. The family, while not wealthy, was comfortably off by the standards of the day. Jane was therefore able to see the latest fashions, buy the most up to date fabrics and trimmings and to have garments made up for her by professional dressmakers. Even so, new clothes were expensive in the early 19th century; Jane and Cassandra paid 17 shillings each to a London dressmaker for new pelisses in 1811. However clothes were often updated with new trimming or by raising or lowering the waistline in accordance with the latest fashion. Garments were also dyed in order to convey the impression of a new outfit, although not always successfully and Jane complained to her sister that one of her gowns fell ‘all to pieces’ after coming back from the dyers. In a letter to Cassandra Jane mentions a visit to Grafton’s, a draper and haberdasher, in April 1811 where she had to wait half an hour before being served but then bought trimming and three pairs of silk stockings at twelve shillings a pair. References to shopping, home needlework and the latest fashions occur in her letters to family and friends, although the subject is only very rarely touched upon in her novels. Perhaps the best known reference to pelisses (and incidentally to the usefulness of the garment) occurs in ‘Persuasion’, Jane’s novel which she finished writing in 1816 although it was published posthumously in 1817, the year of her death. The hero of the story, Captain Wentworth, is describing his pleasure at achieving his first naval command, of an elderly sloop called the Asp. Louisa Musgrove suggests that Captain Wentworth must have been disappointed to see ‘what a very old thing they have given you’. The Captain, however, describes the ship in these terms: - ‘I knew pretty well what she was before that day…I had no more discoveries to make than you would have as to the fashion and strength of any old pelisse, which you had seen lent about among half your acquaintance ever since you could remember, and which at last, on some very wet day, is lent to yourself’. Increasing ill health in her later years, which certainly caused her pain and may have caused some discoloration of her skin, caused Jane to prefer garments with long sleeves. While these could be appropriate for day dresses, evening gowns invariably had short sleeves which would have made the use of a light silk pelisse an acceptable compromise. By 1814 even Jane’s evening gowns were made with long sleeves, but by then the fashions were changing and "Long sleeves appear universal, even as Dress". Jane died at Winchester in July 1817 at the age of 42. She is buried in Winchester Cathedral.